A case report of repair of secondary fracture of proximal metacarpal end of radius and ulna

1. Case Details

1.1 Basic Information

Dog (named Fuhua), 4 years old, male, 12 kg. Date of presentation: April 2, 2009. 1.2 Medical History

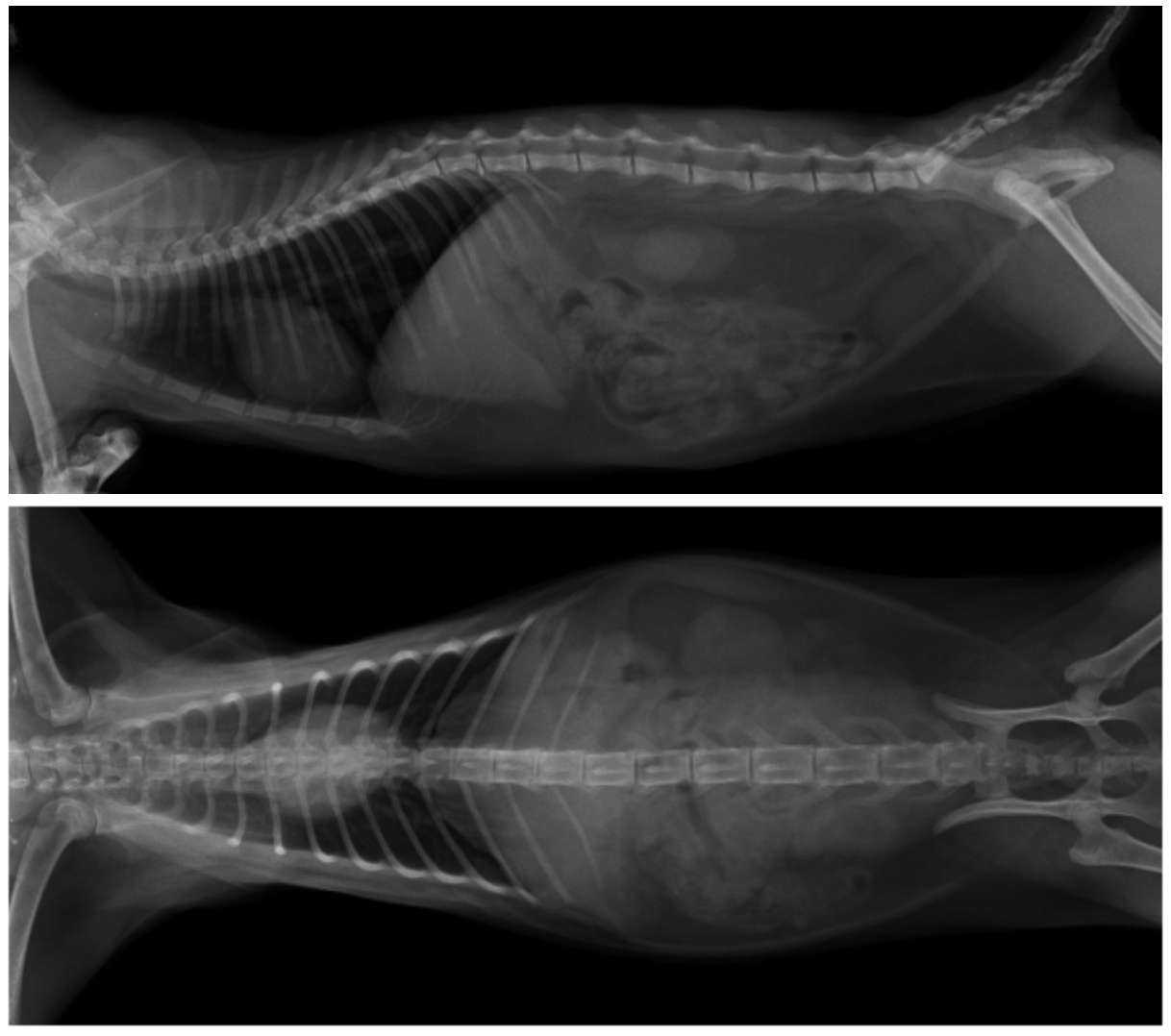

This patient had previously been seen at our hospital on January 17, 2009. At the time, the dog was extremely nervous and afraid to touch the ground with its left forelimb. The patient complained of being hit by a car the previous night. Clinical examination revealed no other abnormalities. To determine the extent of injury to the affected limb, an anteroposterior radiograph of both forelimbs was obtained (see image below, left).

The patient was diagnosed with a transverse fracture of the proximal metacarpal end of the radius and ulna in the left forelimb, requiring internal fixation. Because the owner could not afford the cost of surgery, they opted for external fixation with a splint and subsequently returned home for recuperation. The patient returned to our hospital on April 2, 2009, complaining of slow recovery after undergoing internal fixation at another hospital two months prior. Furthermore, the patient presented to our hospital with postoperative abnormalities and no improvement, leading to the patient's return.

1.3 Clinical Examination

The dog's T, P, and R measurements were normal, and its nutritional status was good. Dietary, bowel, and urinary abnormalities were normal, and its mental state was good. The dog had lameness in the left forelimb, and the limb was severely deformed at the site of the original fracture. A localized medially protrusion measuring 5 x 3 x 3 cm was present. Palpation revealed a firm, non-fluctuating, and painless mass, with intact epidermis.

1.4 X-ray and Laboratory Examination

X-ray examination revealed a 4 x 75 double-hole plate fixed to the right side of the radial stump, with circular ligature wire. The original fracture site was significantly displaced medially and anteriorly in the radius and ulna. Extensive callus had formed at the ulnar stump, and bony hyperplasia was present in the radius. Blood routine and biochemical analysis were essentially normal, with a PLT count of 130 x 109/L (175-500). Neurological examination revealed no significant abnormalities.

1.5 Treatment Plan and Procedure

Summary and Discussion 2.

2.1 Surgical Anatomy, Approach Selection, and Orthopedic Implant Selection

2.1.1 Muscle Groups

The muscles of the forearm and forefoot act on the wrist and finger joints. Their bellies are located on the dorsolateral and palmar surfaces of the forearm. Most are multi-tendon, spindle-shaped muscles that originate from the distal humerus and proximal forearm bones and transition into tendons near the wrist joint. Others are enclosed in tendon sheaths. The forelimb muscles can be divided into the dorsolateral and palmar muscles.

The dorsolateral muscles, from anterior to posterior, include the extensor carpi radialis, extensor digitorum communis, and extensor digitorum lateralis. Deep to the extensor digitorum at the lower forearm, lie the oblique extensors of the wrist.

The extensor carpi radialis extends the wrist and stabilizes the shoulder, elbow, and wrist joints during standing. The extensor digitorum communis extends the fingers and wrist and also flexes the elbow. The lateral extensor digitorum muscles extend the fingers and wrist. The superficial layer of the palmar muscles consists of wrist flexors, including the lateral flexor carpi, radial flexor carpi, and ulnar flexor carpi. The deep layer consists of finger flexors, including the superficial flexor digitorum and profundus flexors. The lateral flexor carpi flexes the wrist and extends the elbow; the ulnar flexor carpi flexes the wrist and extends the elbow; the radial flexor carpi flexes the wrist and extends the elbow. The superficial flexor digitorum flexors flex the finger and wrist during exercise and maintain the angles of the joints below the elbow during standing, supporting body weight. The deep flexor digitorum flexors function in the same way as the superficial flexor digitorum.

2.1.2 Blood Vessels and Nerves

The forelimb arteries and veins originate from the axillary arteries and veins and are distributed throughout the muscles and skin of the forearm. The cephalic vein, which originates from the axillary vein and reaches directly to the ventral side of the wrist joint, has the greatest impact on the surgical site. Special care should be taken when separating the muscles. Injury can easily lead to poor blood supply to the affected limb.

The forelimb nerves include the superficial branch of the circumflex nerve, the distal branch of the ulnar nerve, and the median nerve.

2.1.3 Surgical Approach Selection

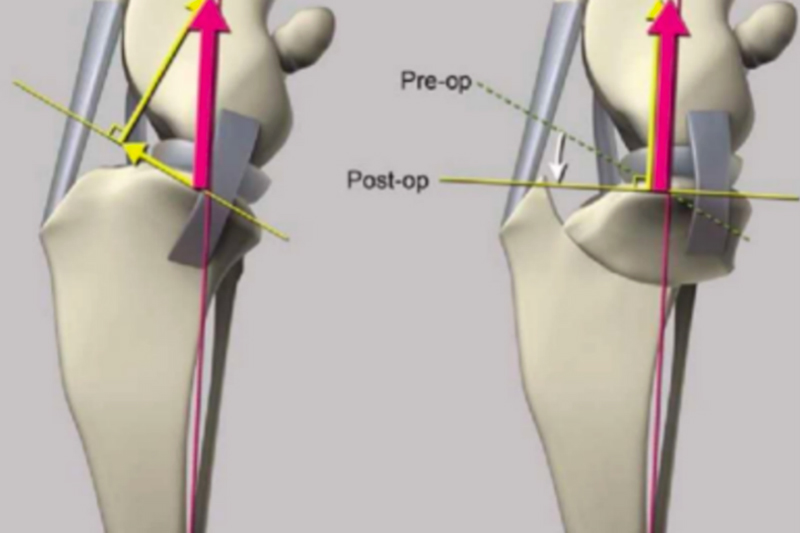

For this type of fracture, two approaches, medial and lateral, are used, depending on surgeon preference. The difference between these two approaches is that the lateral approach provides better visualization of the radial and ulnar structures and has fewer vascular and nerve distributions than the medial approach. In this case, the author believes that the lateral approach is more intuitive, direct, and provides more biomechanically accurate implant stress conditions.

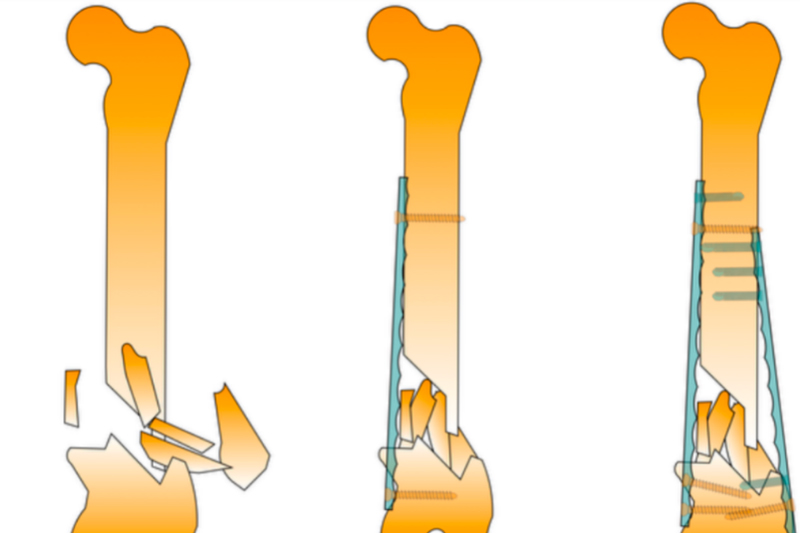

2.1.4 Orthopedic Implant Selection and Implantation

For this type of fracture, plate fixation is recommended. Depending on the dog's size and weight, intramedullary nailing or wire placement can also be used to increase stability and load-bearing capacity. The author believes that a plate with at least three holes should be selected to maximize the parallel alignment of the two fractured bones. In this case, a 4x60 compression plate was selected. Due to the extensive callus formation at the fracture ends, the callus was removed to ensure optimal limb healing. The implant site was chosen to be the anterior median surface of the radius.

2.2 Discussion

2.2.1 Definition

This type of fracture is often caused by a sudden external impact. The animal may limp or hop. Muscle and subcutaneous edema is common during the acute injury phase. Surgery is usually performed 3-5 days after injury, when local swelling has resolved and pain has subsided.

2.2.2 Choice of Fixation Method

Internal fixation is the preferred method for this type of fracture.

2.2.3 Choosing a Surgical Approach

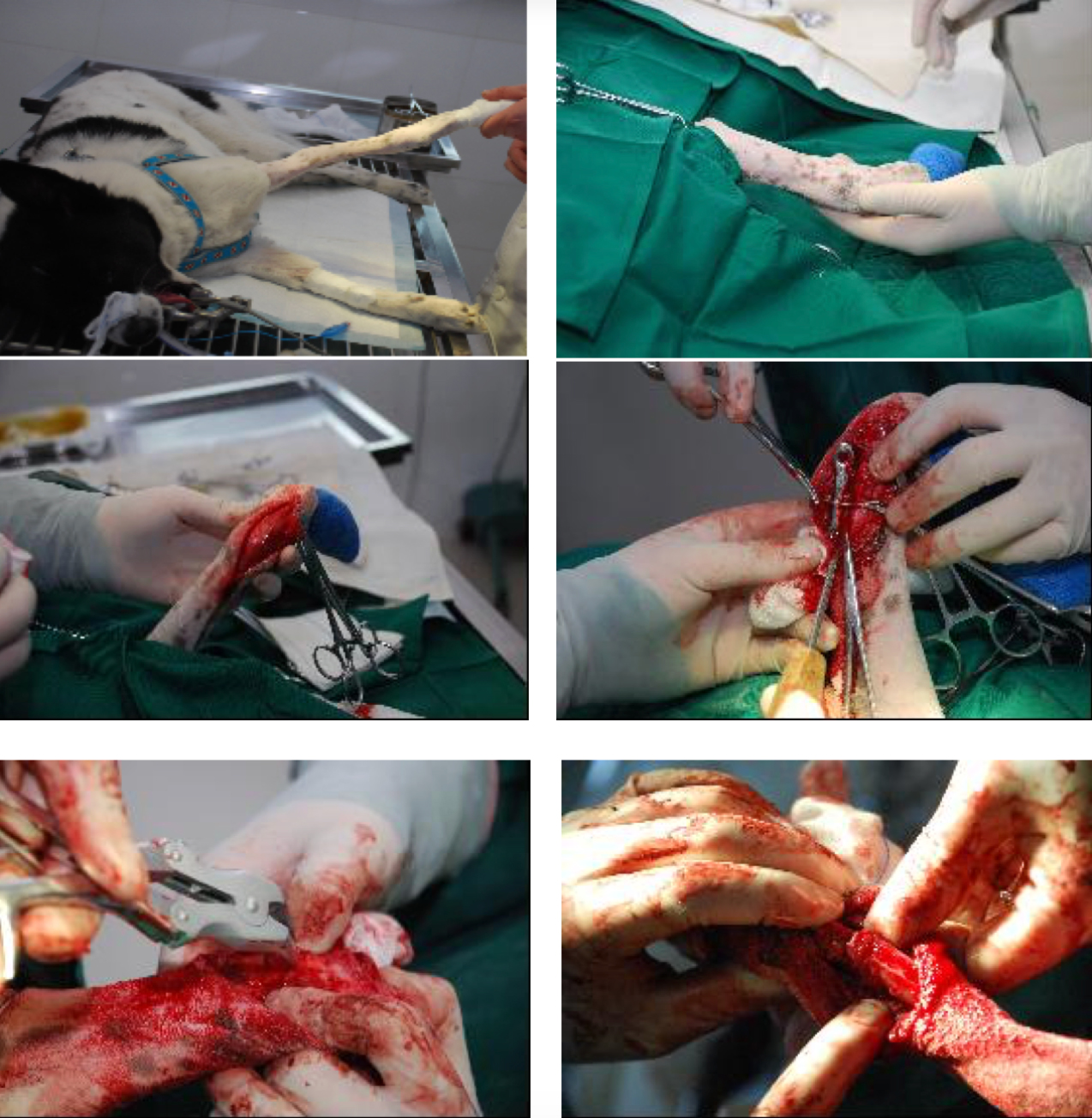

For fracture surgery, the approach we choose should consider the site of injury; the animal species, size, and build; the fracture type; the degree of soft tissue damage and the risk of postoperative infection. We must ensure that the anatomy and physiological function of the surgical site are minimized. In this case, the author believes that the lateral approach offers advantages such as easier dissection, less tissue damage, and easier access to the wound site. 2.2.4 Surgery

The wrist joint should be bandaged with a sterile bandage to prevent contamination of the surgical site and facilitate access. For secondary fracture repair, extensive callus or new bone formation at the fracture ends requires minimal dissection during surgery to avoid compromising surgical quality (in this case, extensive callus growth on the radial and ulnar periosteum significantly increased the difficulty of dissection). Postoperative X-rays are particularly important to ensure adequate fracture reduction and proper implant size and placement (to avoid contamination of the wound during the procedure).

2.2.5 Postoperative Recovery

Strict preoperative evaluation, meticulous intraoperative technique, and meticulous postoperative care are crucial for recovery from fractures. Generally, periosteal hyperplasia and callus formation occur 20 days after surgery; new bone begins to form at the fracture ends 30-40 days later; healing is complete in 3 months; and callus absorption begins after 6 months, ultimately restoring the fracture ends to a flat surface.

2.2.6 Orthopedic Implant Removal

The decision to remove an orthopedic implant depends on the degree of bone healing and the patient's preference.

3. Lessons Learned

The author believes there are three reasons for the failure of the initial surgery in this case: First, the plate selection was inappropriate. The two-hole plate had extremely poor stability. Although the surgeon performed a circular wire ligature on the affected area, the effect was still unsatisfactory. Second, the screws were drilled too shallowly and too close to the stump. Insufficient screw engagement can easily lead to screw dislodgement, while being too close to the stump can also cause the screws to move and fracture the bone. Third, external fixation was not used for this dog. External fixation plays a crucial role after orthopedic surgery, due to its effective load-bearing properties and resistance to torsion and impact. Furthermore, there were some minor errors during the initial surgery, such as the wire ligature method. Due to the smooth surface of the plate, the wire could easily move freely, becoming a burden instead of fulfilling its purpose. Appropriate grooves could be engraved on the intact bone surface to increase the wire's stability. The plate was also trimmed. Damage to the plate itself is highly recommended. These factors also affect the success of the surgery. A successful orthopedic surgery places high demands on the surgeon, the equipment, and the nursing staff. The key factors are as follows:

The surgeon's excellent communication skills: Orthopedic surgery is often expensive, and the patient's psychological differences, financial tolerance, and trust in the hospital's medical technology can directly determine whether the surgery can proceed smoothly.